loss or liberation?

on the rise of anti-intellectualism in music and art, and a bit about the tiktok ban

I close my eyes and it’s 2019: I’m in a coffee shop watching some fourteen-year-old take mindless sips of an iced latte while her phone loops the same fifteen seconds of the song “Nobody” by Mitski. But she doesn’t know it’s Mitski. She calls it “that sad girl TikTok sound”, and for some reason, this designation will feel more real to her than the artist’s real name ever could. We tell ourselves stories about how things change, about how every generation kills something the previous one held sacred. But this particular death feels different. Maybe it’s because I’m involved directly, sort of. I say this with a certain heaviness: I am, undeniably, a cog in this machine. A singer-songwriter whose following was earned through the very platforms I critique (hi TikTok and Instagram), I feel like I exist in a state of constant contradiction. I’ve been a part of the independent music industry for half a decade now, where authenticity has always existed as a commodity to be bought and sold, and every now and then, I begrudgingly realize how my own work becomes a currency in the attention economy.

The brutal truth reveals itself most clearly in the numbers. When I release music that comes from a place of genuine vulnerability — songs written in those quiet, late night moments when truth feels less like a choice and more like an inevitability—they often disappear into the algorithmic void. But turn that same raw emotion into a trendy sound loop, pair it with the right hashtag, frame it in whatever format TikTok’s favoring this week, and suddenly the metrics spring to life. The views climb, the streams accumulate, the algorithm smiles upon your offering. There’s a certain kind of nausea that comes with this realization. The songs themselves, birthed out of moments of authentic emotion — written on bedroom floors, in the kind of silence that only exists after midnight — become nearly unrecognizable in their new, algorithm-friendly forms. And I suppose this is just the truth of being a musician (or an artist of any kind) in the modern age: to betray your own truth for the sake of visibility.

The same platforms that allow us to reach listeners directly, to build communities around our music, call for a transformation of our most honest moments into easily consumable content. We are all merchants now, trading authenticity for attention, depth for reach. I subconsciously began keeping a list of phrases I’ve seen people use when discussing music. This part hits different! Living rent-free in my head! The way it ate and left no crumbs! What actually bothers me about these phrases isn’t simply their vast distance from traditional music criticism—because all criticism evolves — but their insistence on consuming music as moments rather than wholes. The vocabulary is that of consumption, of immediate gratification, and of content to be devoured rather than art to be contemplated.

Every song ever recorded is literally available at the touch of a screen. The mythology of scarcity has been replaced by the mythology of abundance. And despite this abundance, something vital has been lost in this digital promised land, something that becomes apparent when you watch a teenager in a coffee shop scroll through TikTok, pausing only long enough to catch the hook of a song before swiping to the next great thing to catch their attention. Is this how we listen now? In fragments, in loops, in carefully curated moments stripped of their context? But whenever I discuss this predicament with friends who feel the same, it’s as though we get so caught up in our frustration that our conversations miss the entire point. It’s not merely about the death of listeners’ attention spans; this is about a fundamental reimagining of what it means to engage with art in an age when everything is simultaneously accessible and disposable.

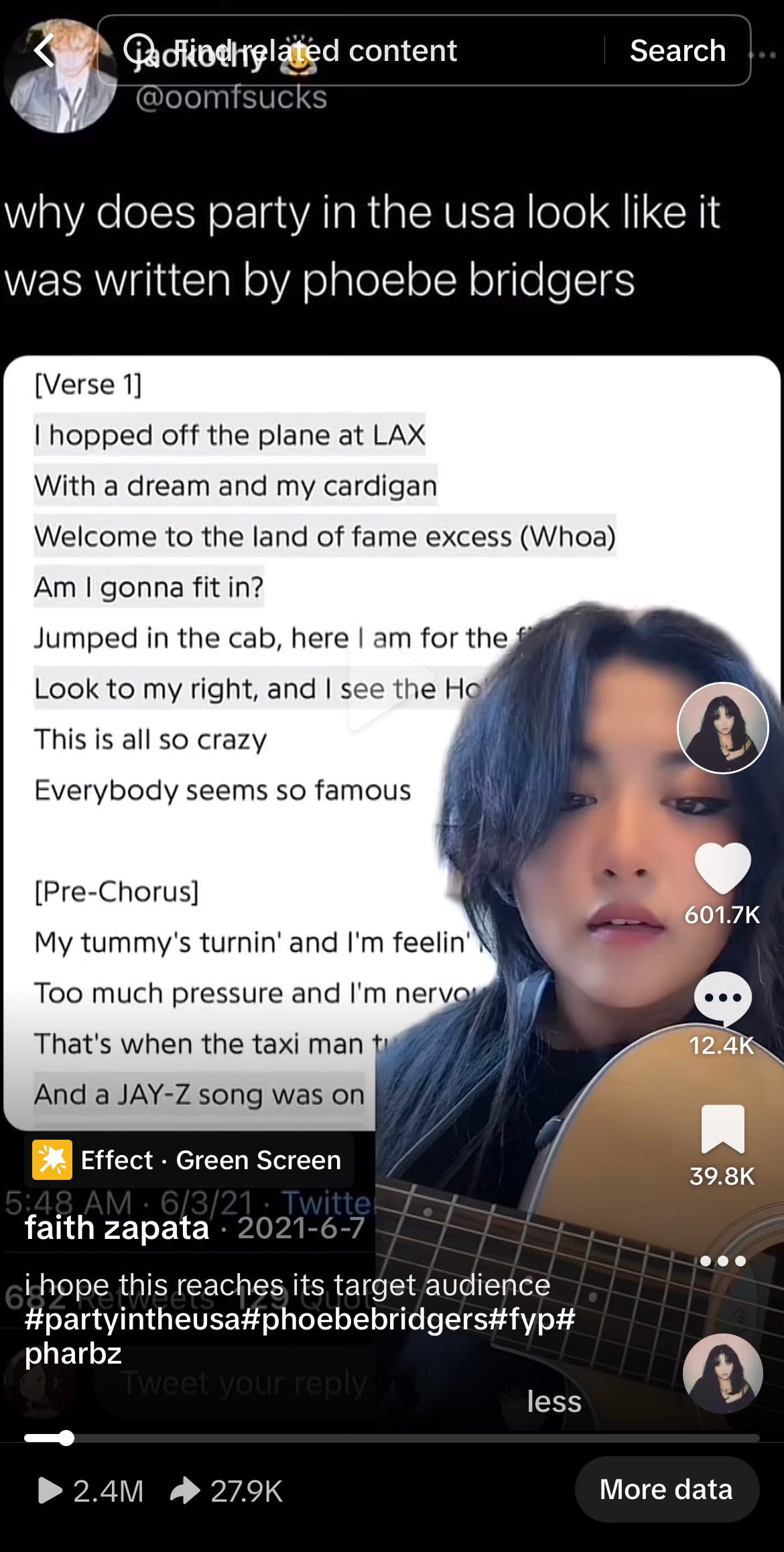

The anti-intellectualism doesn’t manifest through active rejection, but instead within passive incomprehension. Watch a group of chronically online teenagers discuss music: they can tell you the exact timestamp where the Taylor Swift track “All Too Well (10 Minute Version) (Taylor’s Version)” reaches its emotional peak, but only because 3.2 million other users have unanimously agreed that this is the moment of the song that is worth preserving in history. They can recite lyrics out of context, and can recreate viral dance moves with perfect precision, but what they cannot do, what they maybe have never been taught to do, is listen to a song as a complete work of art to begin with. Listeners in the modern age have inherited unprecedented access to musical knowledge but have also somehow been conditioned to view such knowledge as irrelevant. Scrolling past album reviews to find reaction videos, skipping music documentaries to watch fifteen-second clips of their favorite songs recontextualized as background music for makeup tutorials — and the algorithms actually reward this dystopian behavior and provide us with more and more fragments of artwork separated from their entirety.

And now, producers talk about making music TikTok-ready, about engineering songs with moments of popularity in mind. The creative process itself has been altered to accommodate this new way of listening. Artists understand that their work will be carved into pieces, that success depends not on the strength of a complete song but on the potency of its most shareable moment. Even those who should know better (myself included, and most likely, you too) find themselves humming parts of songs they cannot provide a name for if their lives depended on it, referencing snippets of dialogue whose origins they’ve never bothered to go back and trace. The music keeps playing, the remarks keep looping, and the algorithms keep serving up more of what they think we want to hear. And the most painful part is watching genuinely talented artists compete for attention with tracks clearly manufactured for a viral moment. You know the ones — songs that seem to have been built entirely around a catchy hook, where everything else feels like an afterthought, like placeholder verses written only to justify the song’s existence on streaming platforms. When you click through to these viral sensations, the hollowness is blatantly obvious. These songs just collapse underneath the weight of a full listen.

This anti-intellectual mindset hasn’t just changed how we consume music — it has fundamentally altered the relationship between artist and art, creation and presentation. What does it mean to create authentic art in an age where authenticity itself must be optimized for algorithms? What do we lose when we stop listening for the spaces between the notes, when we decide that fifteen seconds to a minute is all we need to know? Sometimes I find myself thinking about all the songs that will never find their audience because they simply don’t fit the format, about all the raw pieces of art that will remain unheard. About all my fellow musicians whose brilliant compositions will never reach the streams of an average hook clearly made for internet virality. Most people will tell you this is fine. That they don’t need the whole song to feel the feeling. Maybe they’re right.

But something honest and vital has slipped away and has been sacrificed at the altar of anti-intellectualism, where depth is seen as merely pretension and complexity as elitism. That sacred space where art exists purely for its own sake and where meaning derives from depth rather than reach simply dissolves into a culture that sees thoughtful listening as unnecessarily cerebral and trying too hard. We might live in an era of unlimited and infinite access, but in this moment, it feels like we have never been further from the heart of music and art — from those intimate instances of honesty that cannot be shrunk to fit the format of whatever platform currently holds our collective attention hostage. The tragedy isn’t only in what we’ve lost (and are still losing), but can also be found in the way most of us seem to have convinced ourselves that this loss — this eradication, this defeat — is actually a form of liberation.

I keep thinking about how telling it is that we’re collectively treating the potential TikTok ban like a death in the family. When I first heard about it, I felt this weird mix of relief and terror that I couldn’t quite place. I think that’s the scariest part; not that we might lose TikTok, but that we’ve become so dependent on its way of seeing that we can’t imagine consuming art any other way.

I really want to believe there’s still hope for deep listening, for art that asks for something more from us than passivity. But mostly I want us to acknowledge what we’ve lost, not just as artists and consumers alike, but as human beings wired with the ability to sit with complexity. And now, with TikTok potentially disappearing, watch how quickly every other platform will rush to fill that void, each one promising to be the new home for viral sounds and trending audio. I mean, it’s already happening; most people have already created a RedNote account and downloaded ZIPs of their TikToks to repost onto Instagram Reels and YouTube Shorts. It’s kind of funny how we're acting like this is some kind of cultural reset when really, we're just trading one algorithm for its slightly different cousin. And I’m definitely not immune to all this: I’ve already done the ZIP folder downloading ceremony, prepared to repost videos of myself singing my little songs onto whatever platform is heir to the throne, in the instance that the ban actually truly does happen once this weekend is over. The platforms might change, but the damage has already been done. We’ve been trained too well.

Maybe we’re not really mourning TikTok. At least I’m not. Maybe we’re mourning a way of experiencing art that we’ve already lost. And whatever platform rises to take its place will just continue what it started: a slow erosion of our ability to sit with depth, to find value in the things that can’t be as easily quantified. And we will adapt, because it’s what we always do.

so sorry that you have to go through all of this as a musician. looking back i also do miss listening to music with process. taking out the casette from its case, rolling it, and read the lyrics on the spread. that was such a beautiful and mindful experience. despite i no longer do that, one of the thing ive been trying to do to be more mindful in consuming music is playing discover weekly playlist on mondays and explore release radar in fridays. carry on with your workk✨

my entire fyp has time travelled back to 2020, with everyone posting drafts and influencers bringing back duet chains. even though tiktok is not disappearing for me, it's so interesting to see how many trends, how many things we've gone through in the past six years (tiktok still feels like a recent app to me, until i realise that 2019 was six years ago and not 1-2). how quickly we've forgotten about them, and how all the memories flood back. "Maybe we’re mourning a way of experiencing art that we’ve already lost." this entire post is so true. short form media has wormed its way through every part and every app of our life- i strongly doubt that the tiktok ban will mean that we consume media in a different way now, because like you said we are simply swapping one out for a similar, parallel app/medium.